Remotes

Goals

By the end of this lesson you should be able to

- Explain how remotes fit into the Git workflow

What is a remote?

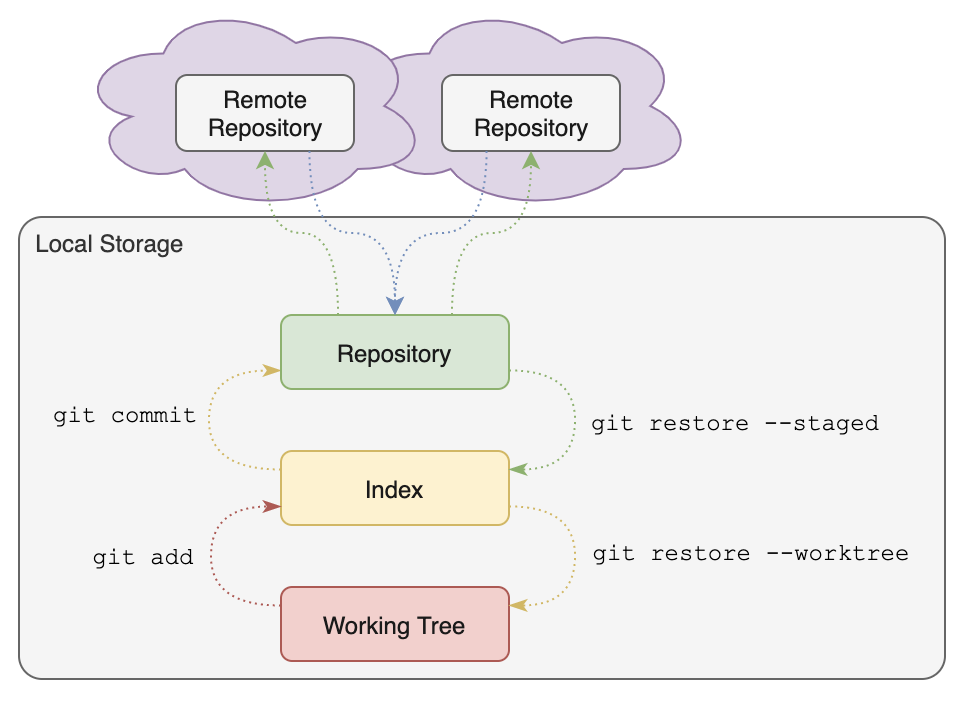

You have already seen how the working directory, index, and repository can be thought of as three ‘layers’ where changes are recorded in Git: the working directory is where you make changes to files; the index is where Git records which changes you want to include in the next commit; and the repository is where Git records the history of commits. All these layers exist within each local copy of a Git repository.

When dealing with multiple copies of a repository, though, there is a fourth layer in the picture: the remote(s).

Definition: A remote for a Git repository is another repository with which a repository can be synchronized.

- A repository and all of its remotes must have shared histories (see the next lesson).

- A remote may exist on the same disk or on a completely separate device.

- A repository may have multiple remotes.

- A repository may pull changes from its remotes, and if the remote is configured correctly may also push changes to its remotes.

Figure: Remotes

This figure summarizes the conceptual relationship between remotes and a local repository.

When you clone a repository, the original repository is configured as a remote for the cloned repository. The remote is labeled origin by default, (but this name may be changed). Git will also automatically configure something called a remote branch for each branch in the remote.

NOTE: The automatic configuration of a remote and its remote branch when cloning is one way in which cloning a Git repository is different than simply copying: no remote repository or branch is automatically configured after a simple copy.

Before taking a closer look at how to manage remotes, we need to discuss a couple new terms that were introduced in this lesson: ‘shared histories’ and ‘remote branches’…